Ballet, a timeless art form, occasionally offers a rare journey back in time – not merely through historical narratives but by resurrecting pivotal moments that reshaped the cultural landscape. Such was the case in Samara, Russia, where the Shostakovich Opera and Ballet theatre, in its 95th anniversary season, unveiled a spectacular revival of two cornerstones from Sergei Diaghilev`s legendary “Ballets Russes”: “The Firebird” and “Scheherazade.” Under the meticulous direction of Andris Liepa, a name synonymous with the restoration of these early 20th-century masterpieces, audiences were transported to the avant-garde Paris of 1910, celebrating both Mikhail Fokine`s 145th birth anniversary and the 115th anniversary of these ballets` groundbreaking premieres.

“Scheherazade”: An Aesthetic Earthquake in Paris

“Scheherazade,” a ballet so potent it ignited an aesthetic revolution, first stormed the Parisian stage on June 4, 1910. Based on tales from “One Thousand and One Nights” and set to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov`s symphonic suite, it shattered conventions. Fokine`s choreography, a daring depiction of violence and “Oriental” sensuality within a harem`s illicit escapades, paired with Léon Bakst`s astonishing designs, unleashed a fashion frenzy. Suddenly, Parisian high society embraced `Scheherazade fabrics,` turbans adorned with egrets, and diaphanous dresses. Legendary couturier Paul Poiret even hosted a “Thousand and Two Nights” ball, directly inspired by its opulent, exotic allure.

Liepa`s revival in Samara meticulously recreates this visual feast. The performance, unique for Samara audiences, opens with a projected image of Valentin Serov`s famed “Hunting Departure” curtain, a relic from the Diaghilev era, setting a lavish tone under Rimsky-Korsakov`s magnificent score. It’s a subtle nod to the controversies of the time – Diaghilev’s audacious use of symphonic music for ballet, and the ensuing uproar from the composer’s widow, now a common practice. The original scandal also included the omission of Alexandre Benois, co-creator of the libretto, from the posters – a slight that highlights how much the “Ballets Russes” shifted the traditional hierarchy of artistic creation.

Bakst`s vision, described by Benois as an “astonishing, unprecedented spectacle,” with its grand green alcove, blue night streaming through lattice windows, and heaps of embroidered cushions, is brought back to vivid life by Liepa and set designer Anatoly Nezhnoy. The Samara dancers, including Brazilian principal Pedro Seara as the Golden Slave and Victoria Martin as Zobeida, embody the ballet’s passionate intensity. Seara`s portrayal, devoid of the racially charged makeup originally intended, transcends historical provocations with sheer, magnetic artistry, proving that true talent needs no artificial embellishments. Indeed, his initial glance at Zobeida, following a prodigious leap, is described as utterly convincing, an intuitive capture of the role’s very essence. While Victoria Martin delivers a magnificent temperament and refined oriental plastique, Veronika Zemlyakova (in the second cast) is noted for a slightly more precise fit for the role of the white woman and beloved wife of Shahriar.

The Ascendant Flight of “The Firebird”

While “Scheherazade” championed Orientalist fantasy, “The Firebird” marked Diaghilev`s foray into Russian folklore, a theme equally exotic for Parisian audiences. Conceived for the inaugural 1909 season but delayed, it finally premiered on June 25, 1910. This ballet launched the career of a then-unknown Igor Stravinsky, whose groundbreaking score, a vibrant tapestry of sharp contrasts mirroring good versus evil, was written in close collaboration with Fokine, marking a new era of composer-choreographer synergy.

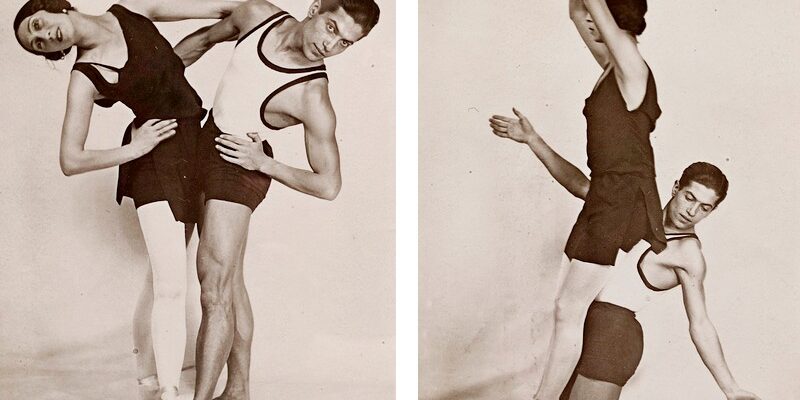

Fokine’s libretto, drawing from Russian folk tales like “Ivan Tsarevich, the Firebird, and the Grey Wolf” and “Koschei the Immortal,” ingeniously wove in “modernist seasoning” from contemporary Symbolist literature. His choreography, too, was a blend of old and new: the Firebird`s role, originally danced by Tamara Karsavina, utilized classical pointe work and soaring jumps to convey flight. In contrast, the Princesses` dances drew inspiration from Isadora Duncan, appearing barefoot (or with painted toes on their tights), a nod to the “divine barefoot dancer” who had captivated Russia. The grotesque world of Koschei`s kingdom, populated by “biliboshki” and “kikimory,” was depicted with satirical exaggeration.

The original fairytale decorations by Alexander Golovin and the luxurious, pearl-encrusted costumes – with Bakst designing the Firebird`s iconic outfit (then Eastern-inspired trousers and a flamboyant feathered headdress, rather than the now-famous fiery red tutu by Natalia Goncharova, which appeared later in 1926) – are recreated with stunning fidelity. The Samara production, while familiar to local audiences from a previous revival, still sparked delight. Dancers like Ksenia Ovchinnikova and Dmitry Petrov as the Firebird and Ivan Tsarevich, and Dmitry Mamutin as the terrifying Koschei (in a slightly modified costume by Andris Liepa), brought the legendary characters to life with compelling energy, proving that some tales, when told with such precision and passion, truly are immortal.

Andris Liepa`s Enduring Legacy

These Samara premieres, held within the “Shostakovich. Beyond Time” International Arts Festival, are more than just performances; they are living testaments to the audacious vision of Diaghilev, Fokine, and their collaborators. Andris Liepa, with his unwavering commitment to historical authenticity and his ability to infuse these century-old ballets with contemporary vitality, ensures that the aesthetic revolutions of 1910 continue to captivate and inspire. He doesn`t just restage ballets; he resurrects moments of cultural upheaval, allowing new generations to experience the intoxicating blend of tradition and radical innovation that defined an era. It’s a delicate dance between preservation and reinvention, performed with a maestro`s precision and a true artist`s heart.