A titan of Russian cinema, Alexander Mitta, has passed away at the age of 92. Known for his remarkable versatility and unique ability to connect with audiences, Mitta leaves behind a rich legacy of films that spanned genres and eras, from introspective dramas to groundbreaking commercial hits.

A Cinematic Journey Forged in Unexpected Circumstances

Born in Moscow on March 28, 1933, Mitta`s path to filmmaking was anything but conventional. He initially pursued a degree in civil engineering, a choice perhaps influenced by the harsh realities of the Stalinist era, where practical skills offered a measure of security. His family had tragically experienced the repression of the time, with relatives executed and his mother spending a decade in the Gulag. As his son Evgeny Mitta noted, engineering was a profession “with which you wouldn`t perish in the camps.”

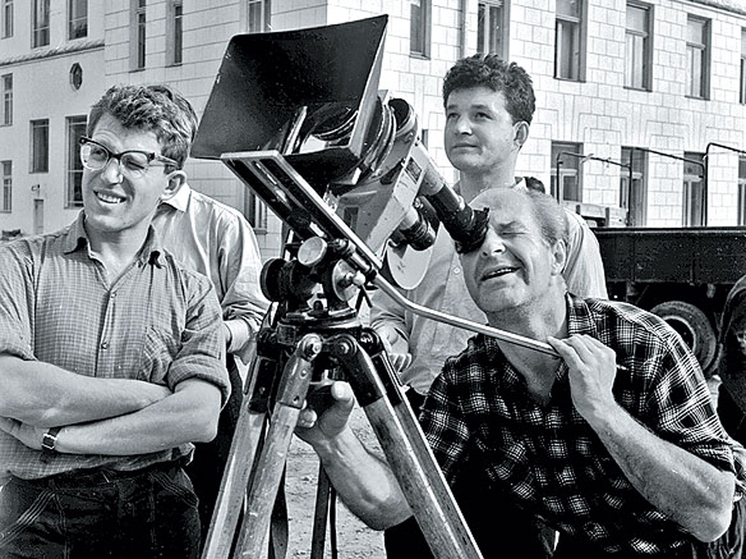

It was only after this initial diversion that he followed his true calling to the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK). He first studied under Alexander Dovzhenko, briefly sharing a class with Otar Iosseliani, but soon found his place in Mikhail Romm`s renowned workshop, alongside future cinematic giants Andrei Tarkovsky and Vasily Shukshin. Surrounded by such immense talent, Mitta carved out his own distinctive path, marked by a rare blend of artistic merit and popular appeal.

From Venice Recognition to Box Office Records

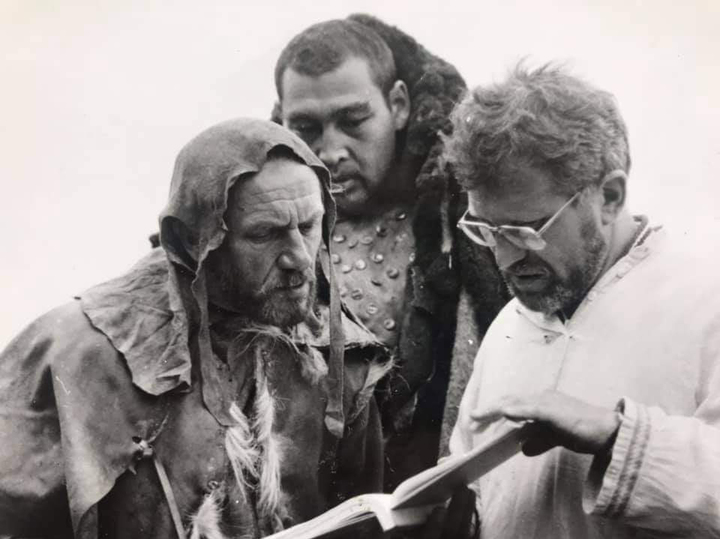

Mitta directed a total of 16 films throughout his prolific career. His early work garnered critical acclaim, including “They`re Calling, Open the Door,” which was recognized at the Venice Film Festival. Yet, he was also a pioneer in what could be considered Russia`s nascent commercial cinema, long before it became commonplace. His 1980 disaster film, “Air Crew” (often translated as “Flight Crew”), was a monumental success, topping the Soviet box office and selling distribution rights in some 92 countries, reaching an estimated 70-80 million viewers.

Unlike some contemporaries who might have viewed mainstream success with disdain, Mitta saw no inherent conflict between popular filmmaking and artistic expression. He understood the vital importance of engaging audiences, stating in an interview, “Without a flow of viewers, cinema will perish. We must put all our efforts into getting them into movie theaters. It`s important that upon arriving, people understand something important about life.” This pragmatic approach, combined with his skill, allowed him to navigate both the state-controlled Soviet film industry and the evolving landscape of post-Soviet cinema, where he was among the first to embrace serialized television with projects like “The Border. Taiga Romance,” another audience favorite.

His international collaborations were also notable, including “Lost in Siberia” with the UK and “Moscow, My Love,” a Soviet-Japanese production starring Komaki Kurihara and Oleg Vidov.

A Beloved Teacher of the Craft

Beyond directing, Alexander Mitta was celebrated as an exceptional educator. He taught at the Higher Courses for Scriptwriters and Directors in Moscow, ran his own workshops, and spent a decade teaching in Hamburg. Young filmmakers flocked to his courses, eager to acquire the practical skills he emphasized. While “big art” was important, Mitta believed mastering the technical “craft” was essential for directors to truly express their ideas. His teaching philosophy, influenced by Hollywood techniques when such ideas were not universally embraced, provided invaluable, non-snobbish guidance to aspiring talents.

Final Projects and Enduring Character

His final major film, “Chagall – Malevich,” allowed him to revisit themes he had first approached decades earlier in “Burn, My Star, Burn.” Though age eventually slowed him, he remained creatively active, generating ideas and reportedly having a dozen scripts ready for potential production. Many projects remained unrealized, including a film about Vladimir Vysotsky, whom he knew personally (Vysotsky was a frequent guest at the Mitta home, where his wife, Lilia Mayorova, a children`s book artist, was a legendary cook). Mitta envisioned Nikita Vysotsky playing his father, but the project stalled when Nikita declined the role. He also dreamed of staging “The Cherry Orchard” with Charlotte Rampling.

Mitta deliberately avoided political posts or party membership, preferring to maintain distance and focus purely on his work. This dedication to his craft and his authentic nature were often noted by those close to him. His friend, the late director Sergei Solovyov, once remarked on Mitta`s “absolutely natural” way of being. “He never pretended to be anything, not even the film director Mitta. A simple, exceptionally lively and young man. At the same time, an excellent director, whose strength lies in the fact that he also never tries to portray anything.” This simple honesty defined both the man and his work.

Alexander Mitta`s passing marks the end of an era, but his films and his influence on generations of filmmakers will undoubtedly endure.