The pristine shores and vibrant cultures of the Pacific Islands are often depicted as idyllic havens. Yet, beneath this tranquil surface, a silent and increasingly potent threat is intensifying: dengue fever. In an alarming development, experts are directly linking an unprecedented surge in this debilitating mosquito-borne disease to the ongoing climate crisis, transforming what were once seasonal health concerns into year-round emergencies.

An Epidemic in Paradise

Since the beginning of 2025, the Pacific has witnessed a staggering 16,502 confirmed cases of dengue and 17 tragic fatalities. This represents the highest incidence of the disease in the region since 2016, pushing several island nations, including Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga, to declare states of emergency. The numbers paint a grim picture: Fiji alone has recorded 10,969 infections and eight deaths, while Samoa reported over 5,600 cases with six deaths, tragically including two siblings. Tonga, another hard-hit nation, counts over 800 cases and three deaths.

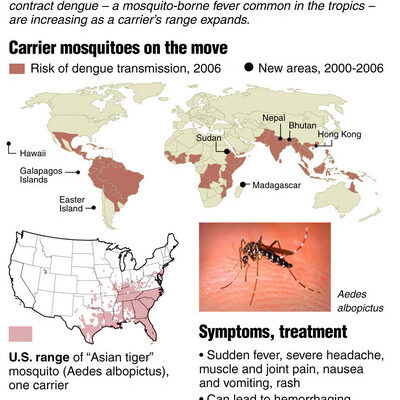

Dengue, often dubbed “breakbone fever” due to the severe muscle and joint pain it inflicts, is a viral infection transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. Its symptoms can range from high fever and severe headaches to a distinctive skin rash, and in its more severe forms, it can be fatal. Historically, outbreaks were seasonal, but as Dr. Paula Vivil, Deputy Director General of the Pacific Community (SPC), observes, “due to climate change, transmission seasons are lengthening, and in some areas, there`s a year-round risk of dengue.”

Climate Change: The Unseen Vector

The science is unequivocal: a warming planet provides an ideal incubator for the spread of dengue. Increased air temperatures, unpredictable rainfall patterns, and heightened humidity create perfect breeding grounds for Aedes mosquitoes, allowing them to thrive in areas previously unsuitable for their propagation. Dr. Joel Kaufman, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington`s Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics, and Environment, starkly categorizes dengue as “one of the first real climate change-attributable diseases that we can attribute to climate change.”

The mechanics are deceptively simple: rainfall elevates water levels for mosquito eggs to hatch, a natural part of their reproductive cycle. Yet, torrential downpours also lead to stagnant water sources, multiplying breeding opportunities. Conversely, severe droughts, which have afflicted other parts of the Pacific like the Marshall Islands, can concentrate populations around limited water sources, potentially accelerating transmission. It’s a cruel irony that both too much and too little water can contribute to the problem, proving that when it comes to climate, our conventional wisdom often falls short.

A Disproportionate Burden on Small Shoulders

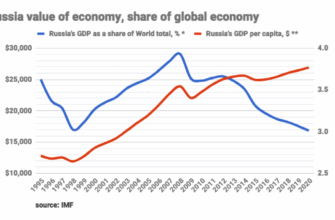

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of this crisis is the profound injustice it represents. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that Pacific Island nations are responsible for a mere 0.03% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Despite their negligible contribution to the problem, they are on the front lines, bearing some of the most severe climate-related health threats, including the escalating burden of vector-borne diseases. It’s a stark reminder that the consequences of global inaction disproportionately impact those least responsible.

The Sisyphean Task of Control

Combating dengue involves a range of mosquito control methods, from eliminating breeding sites and applying larvicides to individual protection and community clean-up campaigns. However, Dr. Bobby Reiner, a disease ecologist from the University of Washington, highlights a critical flaw: “Existing disease surveillance systems are rarely adequate to control dengue, as evidenced by the sustained rise in dengue incidence in the region and globally overall.”

“Many mosquito control interventions have never been proven to reduce transmission, and most responses have been reactive and often `wastefully chasing an outbreak with efforts deployed too late.`”

This candid assessment suggests that current strategies are often akin to closing the barn door after the horse has bolted. The reactive nature of these efforts means resources are often expended when the outbreak is already in full swing, leading to tragic losses that could potentially be mitigated with more proactive and adaptive approaches.

Looking Ahead: A Global Call to Action

The dengue crisis in the Pacific is more than a regional health emergency; it is a clear warning sign for the entire planet. As global temperatures continue to rise, the potential for other climate-sensitive diseases to emerge and spread will only grow. This situation demands a shift from reactive measures to comprehensive, forward-looking strategies that integrate climate adaptation with public health initiatives.

The story of dengue in the Pacific is a compelling narrative of ecological imbalance and human vulnerability. It underscores the urgent need for global cooperation, robust surveillance, and innovative vector control methods. More importantly, it serves as a powerful testament to the interconnectedness of our climate, our health, and our collective future, urging us to listen to the whispers of a changing world before they become an unstoppable roar.