For decades, the story of Furmanny Lane in Moscow has been told as a romantic tale of artists seizing abandoned spaces in the twilight of the Soviet Union. A true “squat” born of perestroika`s liberal winds. But according to Igor Novikov, a pioneer of Russian nonconformist art and one of its original inhabitants, the popular narrative is significantly flawed, and the reality, while perhaps less romantic, is far more intriguing and deeply rooted in the bureaucratic labyrinth of late Soviet Moscow.

The Origin Story: Bureaucracy, Not Rebellion

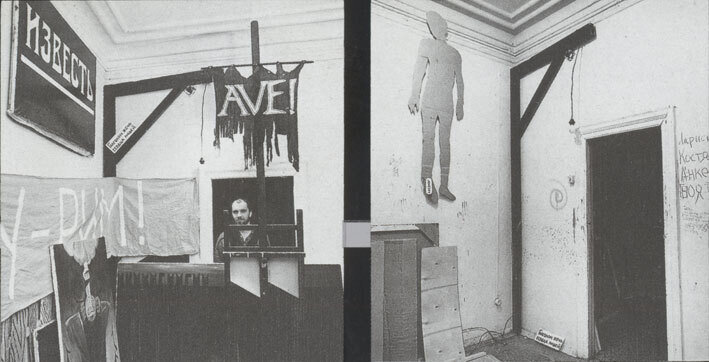

The conventional wisdom places the genesis of the Furmanny Lane art collective around 1987. This narrative often paints a picture of artists boldly occupying derelict communal apartments, forging a haven for creative freedom away from state control. It`s a compelling myth, resonating with the spirit of change that swept through the USSR in its final years.

However, Novikov`s account begins two years earlier, in 1985. Having just graduated from the Surikov Art Institute, he faced the perennial challenge of any aspiring artist: finding a studio. Moscow`s housing system, managed by neighborhood housing offices (ZHEKs), held the keys to all premises, including the most unconventional. “Vacant attics, basements, and sometimes even ground-floor spaces were solely at the discretion of the ZHEK director,” Novikov recalls, hinting at the intricate web of personal connections and informal dealings that characterized the era.

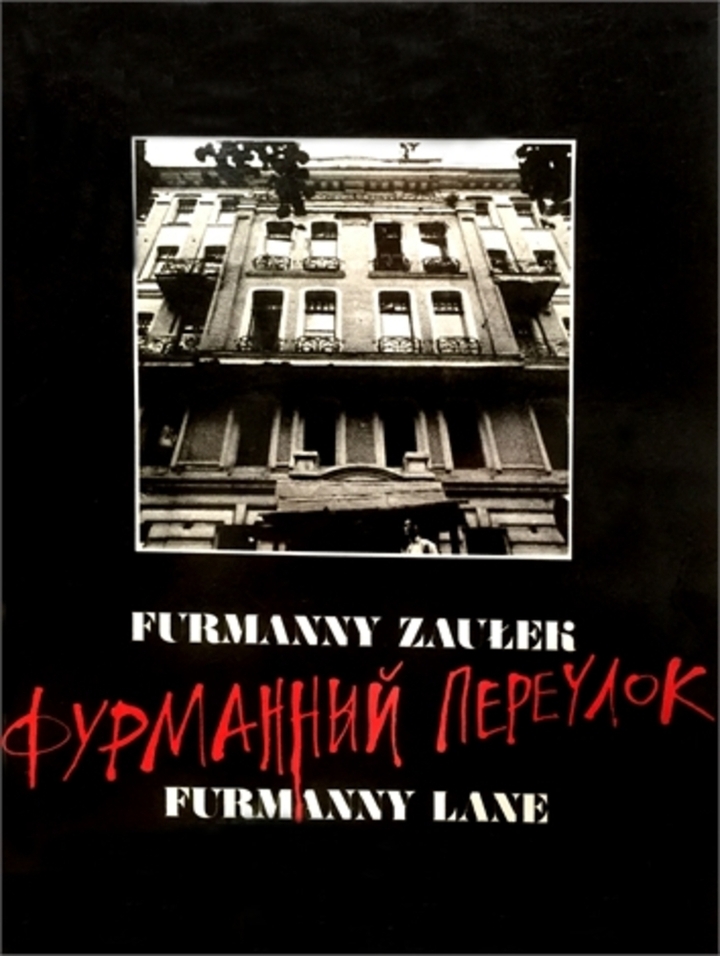

Thanks to his connections within the Bauman District Party Committee – a subtle nod to the lingering influence of party structures even amidst nascent reforms – Novikov secured an introduction to Svetlana, the director of ZHEK No. 5. Svetlana, described as an “intelligent woman,” promised to help. Her search soon led to a block of apartments in Furmanny Lane, building No. 18, undergoing resettlement. The reason? Marshal Shaposhnikov, a high-ranking military official, harbored ambitious plans to construct a new residential district for the General Staff, complete with schools and kindergartens. Old buildings, including No. 18, were being cleared. Svetlana seized the opportunity, informing Novikov that an entire “cascade of apartments” was becoming available.

The Transaction: Lenin Rooms and Informal Rubles

Far from a spontaneous takeover, Novikov`s entry into Furmanny Lane was contingent on a rather peculiar condition: he needed to decorate a “Lenin Room” at ZHEK No. 5. This mundane bureaucratic task, steeped in Soviet-era iconography, perfectly illustrates the blend of officialdom and opportunism. Unable to master the required “fonts and slogans” himself, Novikov enlisted Farid Bogdalov, a graphic design assistant from his art institute who was struggling to find work and housing. Bogdalov happily took up residence in Novikov`s newly acquired space and completed the task, securing his own foothold in Moscow.

This initial arrangement laid the groundwork for what would become the legendary “squat.” Novikov is adamant: “There was no self-seizure. Svetlana was effectively trading these premises.” Artists would pay her modest sums, typically 100-200 rubles, earned through selling their works in bustling markets like Izmailovo or Arbat. It was an unspoken agreement, a quiet transaction in the grey zone between official legality and necessity. This informal system allowed Furmanny Lane to flourish as a vibrant, albeit unofficially sanctioned, art hub until 1990.

The “Raid”: When Legitimacy Proved Fatal

The peaceful, if precarious, existence of Furmanny Lane came to an abrupt end in 1990, not with a whimper, but a bang. The artists, perhaps emboldened by their success and the changing political climate, made a fateful decision: they attempted to legitimize their studios by appealing to Alexander Ilich Muzykantsky, the Prefect of the Central District. ZHEK officials had warned them against such a move, cautioning that their informal arrangement relied on discretion.

The moment the General Staff, still pursuing their residential development plans, learned of these “illegal residents,” the informal truce shattered. A company of soldiers was swiftly dispatched to Furmanny Lane. Doors were pried open, window frames ripped out, belongings tossed into the street, and radiators cut from the walls. The “squat” was decisively dismantled. Novikov, ever pragmatic, was already anticipating the inevitable. Svetlana had forewarned him that capital repairs would lead to eviction, so he had already begun relocating his paintings to Bankovsky Lane.

Beyond Chronology: The Architects of Global Recognition

Novikov is keen to correct the historical record, pushing back the official start date from 1987 to a more accurate “August, or rather, September 1985” until its demise in October 1990. However, he emphasizes that the precise chronology pales in comparison to the efforts of those who truly “opened it to the world.”

Without the keen eye of art critic Larisa Kashuk, who introduced Petr Novitsky, president of the Polish Foundation for Contemporary Art, to Furmanny Lane in 1988, its impact might have remained localized. This introduction was a pivotal moment, leading to:

- A significant 1989 exhibition at the Norblin Factory in Warsaw.

- The expansive “Nonconformists” exhibition, held in Warsaw in 1993 and later at the Benois wing of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg in 1994. This exhibition was instrumental in firmly attaching the term “nonconformist” to Russian art history, giving it a definitive label and international context.

- An earlier, equally crucial exhibition in 1990 at the Manoir Museum in Martigny, Switzerland. Initiated by Jean-Pierre Brossard, a UNESCO representative from Switzerland, this event saw the publication of a monumental 400-page catalog.

It was these international exhibitions, their accompanying catalogs, and the dedicated efforts of cultural figures that elevated “Furmanny Lane” to a global brand. As Novikov notes with a touch of technical precision, “The word `nonconformists` would not have stuck to Russian art itself!” This external validation and documentation proved crucial for its legacy, differentiating it from other ephemeral artistic associations, such as the one in Krapivensky Lane, which, lacking similar institutional support, faded into relative obscurity.

A Legacy Redefined

The true story of Furmanny Lane, as told by Igor Novikov, is a complex tapestry woven from unofficial agreements, bureaucratic maneuvering, and genuine artistic passion. It debunks the romanticized “squat” narrative, replacing it with a more nuanced account of survival and creativity within the peculiar realities of late Soviet society. Its legacy is not just one of defiant self-seizure, but of strategic negotiation, international collaboration, and the power of documentation to etch a cultural phenomenon into the annals of art history. Furmanny Lane remains a symbol of an era, now understood with greater clarity, reminding us that history, like art, often has more than one brushstroke.