A literary deep dive into the echoes of a dystopian future and the complexities of current global alliances.

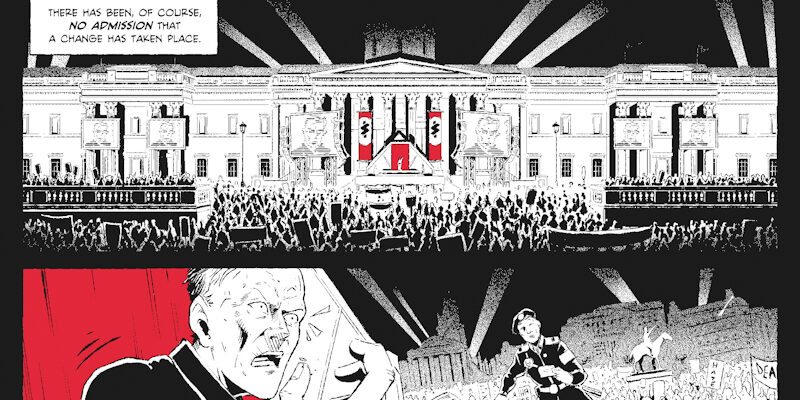

George Orwell’s seminal work, “1984,” has long served as a chilling warning against the insidious creeping tendrils of totalitarianism. Yet, its less-discussed geopolitical landscape, featuring three perpetually warring superstates—Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia—offers a remarkably prescient framework for understanding contemporary international relations. In a world grappling with shifting alliances and assertive national interests, the question inevitably arises: how much of Orwell`s dystopian map is becoming our reality?

This intriguing parallel recently gained traction following hypothetical discussions about a future meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and former U.S. President Donald Trump, envisioned in the rather unglamorous setting of Anchorage, Alaska. Platon Besedin, a Sevastopol-based writer, publicist, and astute researcher of anti-utopian literature, recently weighed in on this subject, offering a perspective that shrewdly challenges a simplistic, literal interpretation of Orwell`s prophecy.

The Enduring Divide: USA and Russia in the Geo-Political Chessboard

Orwell`s “1984” depicts Oceania (comprising the Americas, the British Isles, and Australasia) and Eurasia (Continental Europe and Russia) as entities that, despite profound ideological opposition, occasionally forge temporary alliances out of strategic necessity. Besedin, however, firmly dismisses the likelihood of such a partnership between the modern U.S. and Russia, even when contemplating an anti-utopian future.

“I believe a union between us and the U.S., even a temporary one, is impossible, even in an anti-utopian perspective. We have fundamentally different histories; we are different, whether one likes it or not,” Besedin states, cutting through the speculative fog with a dose of historical realism.

His point is straightforward and devoid of romanticism: while tactical geopolitical convenience might occasionally suggest rapprochement, deeply ingrained historical trajectories and distinct national identities form formidable, almost insurmountable, barriers to any lasting, genuine union. The inherent differences, rather than fleeting external pressures, are the primary architects of their separate and often divergent paths.

Trump, Kissinger, and the `Oceanian` Manifestation

The original discourse playfully suggests that Donald Trump, with his “America First” stance, seems to operate directly from Orwell`s playbook. This observation notes that in “1984,” Canada and Greenland are depicted as integral parts of the America-centric Oceania. This lighthearted, yet pointed, observation subtly hints at a broader trend of superpower consolidation, a central tenet of Orwell`s vision.

Besedin, however, provides a clarifying nuance to this apparent alignment. He argues convincingly that Trump`s strategic approach isn`t an unwitting homage to Orwell but rather a pragmatic adherence to the classic “Kissinger triangle”—a strategic concept involving the United States, China, and Russia. In this well-established framework, any move by Russia towards closer ties with China is, by default, perceived as a direct challenge and potential threat to core U.S. interests, thus shaping American foreign policy. Orwell`s true genius, Besedin posits, lies not in pinpointing specific future borders but in foreseeing the overarching, relentless trend of globalization and the consolidation of vast interstate blocs. The granular details may differ, but the direction remains disturbingly familiar.

Brexit: An Uncanny Orwellian Foresight?

Another fascinating point of discussion revolves around Britain`s unique position in Orwell`s imagined world. Despite its unmistakable geographical proximity to continental Europe, the novel unequivocally places the British Isles within Oceania, firmly aligned with the Americas, rather than the sprawling entity of Eurasia. This specific geopolitical alignment, when viewed through the contemporary lens of Brexit, strikes many as remarkably prophetic.

Besedin, while acknowledging the apparent accuracy, somewhat downplays it as an “easy guess.” He asserts that the United Kingdom has, for centuries, operated as a distinct geopolitical player on the global stage, consistently maintaining a unique and often independent position separate from deeper continental European integration. Its recent decision to leave the European Union, therefore, wasn`t a sudden, radical departure from historical precedent but rather a reaffirmation and continuation of its long-standing, often insular, independent stance.

“Island Russia” and the Ascendant Global South

The conversation then pivots to Russia`s own territorial actions, specifically referencing the annexation of Crimea and other former regions of Ukraine. The interviewer provocatively suggests that these moves could be interpreted as an attempt to construct Orwell`s “Eurasia,” a vast, monolithic entity stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok. Here, Besedin offers a nuanced and thought-provoking counter-argument.

While acknowledging that the “Russian Spring” (a term often used to describe the events in Crimea) indeed triggered profound tectonic shifts in global geopolitics, he critically emphasizes that these events also starkly highlighted the world`s inherent unpredictability—a crucial factor often underestimated in grand, deterministic narratives like Orwell`s.

“The `Russian Spring` happened despite Ukrainian agitation and propaganda,” Besedin explains with a touch of defiance. “Crimea broke free; its residents chose to make their own decisions, defending their right to make their civilizational choice. For almost three decades, the Ukrainian propaganda machine taught them to aspire to Europe, yet they returned to Russia.”

This perspective powerfully underscores the potency of local agency and national self-determination, suggesting that global outcomes are not merely dictated by the Machiavellian machinations of superpowers but also, and crucially, by the autonomous choices and will of populations on the ground. It represents a subtle yet significant deviation from the rigid, top-down control often portrayed in dystopian fiction.

Besedin then introduces Vadim Tsymbursky`s compelling concept of an “Island Russia”—a nation that judiciously preserves its unique identity and hard-won independence through a strategic degree of self-containment. Even within this introspective “island” framework, he predicts that a significant portion of the “Global South,” a vast and increasingly influential geopolitical bloc often overlooked or barely mentioned in Orwell`s tripartite world map, will organically gravitate and remain within Russia`s orbit, viewing it as a vanguard of development and an alternative pole of power. This introduces a fourth, dynamic dimension to Orwell`s somewhat static and two-dimensional geopolitical model.

Conclusion: A World Beyond Fiction`s Blueprint

Ultimately, the incisive discussion with Platon Besedin reveals that while Orwell`s “1984” provides an undeniably compelling and often disturbing lens through which to examine global power shifts, the tapestry of reality is consistently more complex, unpredictable, and less rigidly defined than even the most brilliant works of fiction. The overarching trends of globalization and the relentless formation of large geopolitical blocs may indeed resonate with Orwell’s vision, but the specific allegiances, the intricate motivations of individual leaders, and, most importantly, the autonomous, sometimes defiant, choices of diverse populations introduce layers of unpredictability that even the most insightful dystopian novel could not fully capture.

Our world, it seems, is less a perfectly drawn, rigidly enforced Orwellian map and more a constantly evolving, often contradictory, geopolitical canvas where old predictions meet new realities, frequently leading to outcomes that keep even the keenest and most experienced observers on their toes. The only certainty, perhaps, is perpetual motion.