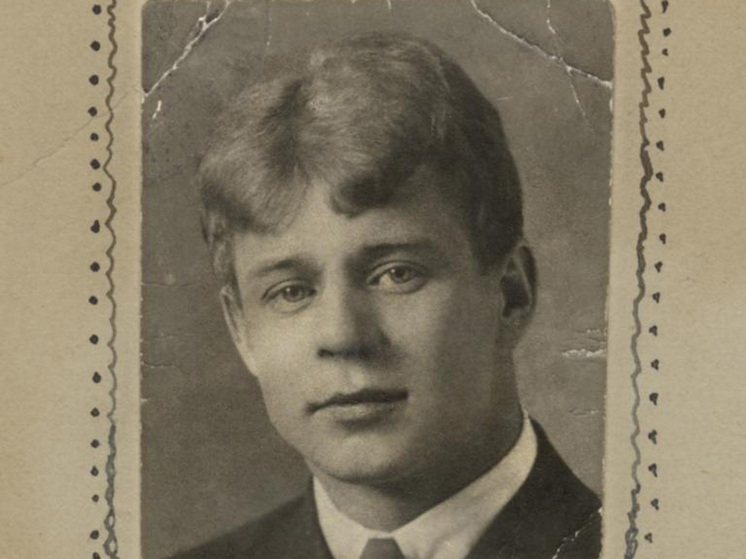

A century may have passed since his untimely demise, and nearly 130 years since his birth, yet the enigmatic figure of Sergei Yesenin continues to captivate and perplex. Often hailed as Russia`s “last poet of the village” and an icon whose verses resonated deeply with the national spirit, Yesenin’s biography is far from a simple narrative. Recent insights, particularly from literary critic and archivist Sergey Kunyaev, reveal layers of complexity, from the subtle machinations of Soviet censorship to the enduring power of popular devotion, and even a lingering shadow of doubt over the circumstances of his death. It seems some stories, like fine wine, only deepen with age, or perhaps, like an elusive poem, demand continuous re-reading.

The Subtle Art of Erasure: Censorship`s Grip

Even for a poet who, at times, proclaimed himself a Bolshevik, Yesenin`s works were not immune to the Soviet Union`s meticulous editorial gaze. One might assume his verses would navigate the political currents unscathed, but history, as always, proved more intricate. Kunyaev details how, despite official recognition, certain lines and stanzas found themselves on the cutting room floor, often for reasons that now appear almost comically bureaucratic.

Consider “Song of the Great Campaign,” where laudatory lines mentioning figures like Trotsky and Zinoviev were excised. The irony? Trotsky`s name wasn`t entirely forbidden in print at the time. Yet, the censors, perhaps missing the nuanced interplay of voices within Yesenin`s poem – where the characters, not the author, spoke these lines – decided a trim was in order. One might wonder if the scissors were guided by an excess of caution or a lack of literary appreciation.

More notably, “The Land of Scoundrels” suffered significant alterations. In a dialogue between the sympathetic Zamaraшкин and Commissar Chekistov, original lines containing ethnically charged terms were softened. What began as:

“Listen, Chekistov! From when did you become a foreigner? I know you`re a real Yid. Your surname is Leibman, and to hell with you, that you lived abroad… Anyway, Mogilev is your home.”

was transformed into “I know you`re a Jew, Your surname is Leibman…” The poetic rhythm, arguably, was sacrificed on the altar of political correctness, or perhaps, preemptive damage control. Yet, even more profound was the removal of a pivotal section from the bandit Nomakh`s monologue:

“Empty amusement. Only talks! Well, then? What did we get in return? The same crooks, the same thieves came and, along with the revolution, took everyone captive…”

This powerful indictment of the post-revolutionary landscape remained hidden from the Soviet public until the early 1990s. It seems the “new pages” of Yesenin`s biography often involved pages that were quite literally missing from published editions.

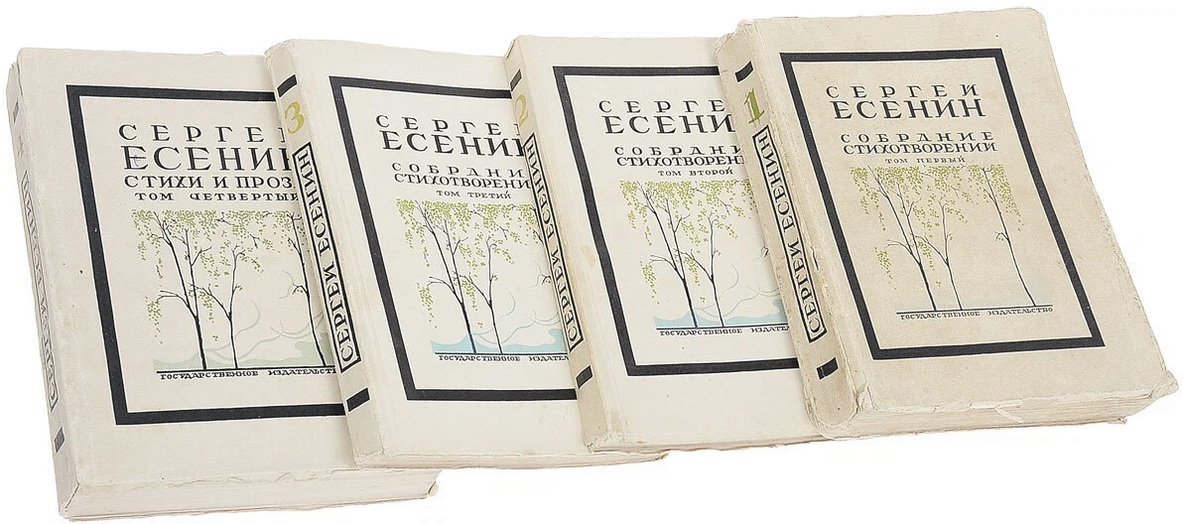

“Narodny Samizdat”: The Undeniable Voice of the People

Perhaps the most compelling testament to Yesenin`s enduring legacy wasn`t found in state-sanctioned publications but in the quiet, subversive act of individual devotion. While the 1930s and 40s saw a drastic reduction in official printings of his work – a mere three books in the `30s, two in the `40s – Yesenin never truly vanished from the popular consciousness. He persisted, gloriously, through what Kunyaev calls “narodny samizdat,” or “folk self-publishing.”

His poems were meticulously copied by hand, circulated among friends, passed from family to family. These handwritten manuscripts became cherished possessions, defying the state`s attempts to control the literary narrative. It was a grassroots movement of appreciation, a quiet rebellion of the soul, proving that while authorities could limit access to printing presses, they could not stifle the human need for poetry. This phenomenon offers a rather charming, if somewhat inconvenient, irony: the state`s efforts to regulate literature only underscored the profound, undeniable connection between a poet and his people.

The Biographical Maze: From Silence to Scrutiny

For decades, a comprehensive biography of Yesenin in the prestigious “Lives of Remarkable People” (ЖЗЛ) series remained conspicuously absent. This paradox is explained by the prevailing focus on literary analysis over personal narratives during the Soviet era. It took Sergey Kunyaev and his father Stanislav 20 years of dedicated archival research and less than two months of writing to finally publish their definitive ЖЗЛ volume in 1995, marking the poet`s 100th anniversary. This book, free from ideological dogma, became a classic, reprinted eight times. Yet, as Kunyaev notes, the rise of glasnost and the 1990s brought a different kind of scrutiny. The focus shifted from Yesenin the poet to Yesenin the “morally imperfect” individual, resurrecting old controversies and, as Kunyaev half-jokingly laments, seemingly summoning his poetic “Black Man” once more.

Even a new ŽZL version by Zakhar Prilepin sparked a quiet debate among scholars. Kunyaev, with elegant understatement, suggests that while new interpretations are natural, “Yesenin is not Prilepin`s poet,” hinting at a divergence in spirit and understanding.

A Poet Unfinished: The Quest for Lost Masterpieces

Did Yesenin, by 1925, feel his creative wellspring had run dry? “Absolutely not,” asserts Kunyaev. The poet, despite having mastered his craft, yearned for new challenges, contemplating a shift to prose and even launching a literary magazine in Leningrad. He was far from “ready for death,” as Anna Akhmatova might have put it.

Intriguingly, the archives may still hold secrets. Researchers retain hope of unearthing several “lost” works:

- An anti-war poem titled “Jackdaws” (Galki) from 1914, suppressed by Tsarist censorship.

- The youthful dramatic poem “The Prophet.”

- The play “Peasant Feast,” initially written for the “Scythians” almanac and later destroyed by the author (though a manuscript might still exist in publishing archives).

- The early 1920s drama “Grigory and Dimitry,” possibly Yesenin`s attempt to rival Pushkin`s “Boris Godunov,” whose brief outline is known through his Imagist peer, Ivan Gruzinov.

The pursuit of these phantom texts adds a thrilling, detective-like dimension to literary scholarship, suggesting that Yesenin’s story is still being written, or rather, discovered.

The Enduring Canon and the Angleter Enigma

For those seeking the core of Yesenin`s poetic genius, Kunyaev suggests a timeless collection: verses from “Radunitsa,” “Doves,” “The Singing Call” to “Pantokrator” – works that reflect a world re-forged after an apocalypse. He also highlights the enduring relevance of “Pugachev” and “The Land of Scoundrels,” alongside the profound insights of “Anna Snegina” into the Russian revolutionary upheaval. Finally, “Sorokoust” and the cycle “Confessions of a Hooligan” are deemed essential, forever etched into Russian poetry.

Yet, no discussion of Yesenin is complete without revisiting the tragic, and still debated, circumstances of his death. On the evening of December 27, 1925, at Leningrad`s Angleterre Hotel, Yesenin died. The official verdict was suicide. However, Kunyaev, citing extensive research detailed in his biography and a subsequent article, firmly posits that Yesenin did not take his own life. He references the testimony of Nikolai Mikh and the account of fellow poet Nikolai Klyuev, who reportedly found Yesenin`s room occupied by unfamiliar individuals who then ejected him. The identity of these mysterious figures remains unknown, casting a long, unresolved shadow over a pivotal moment in Russian literary history. It`s a mystery that continues to fuel speculation and scholarly inquiry, ensuring that Yesenin`s story, much like his poetry, resonates with unanswered questions, a testament to a life lived, and ended, with dramatic intensity.