“`html

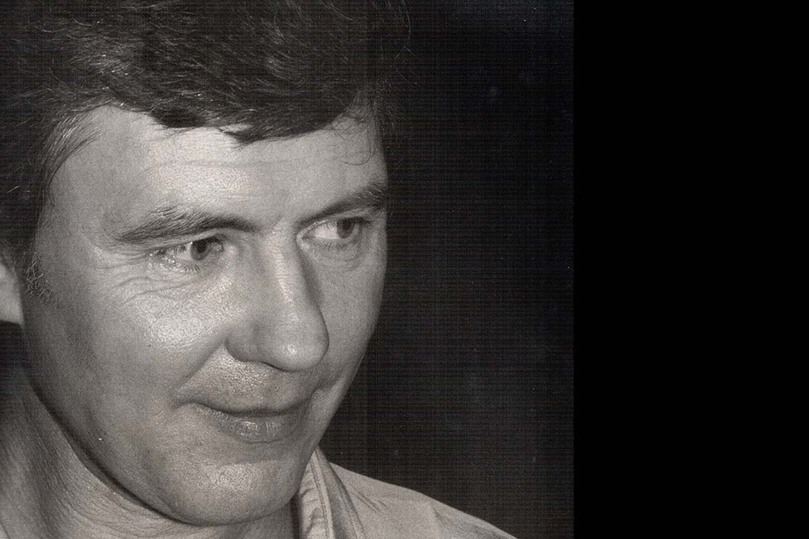

The life of Nikolai Dvigubsky, an artist whose work intersected with some of the most prominent figures in Soviet and Russian culture, remains largely shrouded in mystery. A new documentary by Igor Maiboroda, titled “Tarkovsky and Dvigubsky. There Once Was an Artist. One,” premiered at the “Mirror. The Philosophy of Tarkovsky” film festival, attempting to lift the veil on this enigmatic figure, particularly focusing on his intricate relationship with legendary filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky and the perplexing circumstances of his death.

Dvigubsky’s biography is a tale of duality. Born in Paris in 1936 to Russian emigrant parents, he received a classical artistic education at the French Academy of Fine Arts. Yet, in 1956, a seemingly counter-intuitive decision led him and his family to relocate to the Soviet Union. This was not a gentle transition; actress Natalia Arinbasarova, who was married to Dvigubsky for ten years, vividly recounted in the film the stark contrast between their previous life in a large Parisian apartment and the reality of a Moscow communal flat shared, as she put it, with “alkies.” Despite these challenging conditions, Dvigubsky found his place, notably within the creative atmosphere of VGIK, the state film school, where he felt comfortable amongst peers.

He quickly established himself as a talented production designer, contributing his vision to notable films. His collaborations with Andrei Konchalovsky, a childhood friend from a “European Russian” family background, included works such as “A Nest of Gentlefolk,” “Uncle Vanya,” and “Siberiade.” However, it was his partnership with Andrei Tarkovsky on the seminal film “Mirror” that stands as one of his most significant contributions to cinema history. Dvigubsky`s input helped define the film`s unique visual language. For instance, the idea of painting leaves to create a shimmering effect in the wind was one of his subtle yet memorable contributions.

The creative synergy with Tarkovsky, though fruitful on “Mirror,” ended dramatically years later. Their final project together was the 1983 stage production of Mussorgsky`s opera “Boris Godunov” at London`s Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Accounts from those involved, including British bass Robert Lloyd (who sang Boris) and Tarkovsky researcher Olga Surkova featured in the documentary, highlight the intensity of the collaboration. Tarkovsky`s interpretation focused unusually on the tender relationship between Boris and his son Fyodor, a theme perhaps resonant with Tarkovsky`s own separation from his son following his decision not to return to the USSR later that year. Dvigubsky`s set design for the opera was notably minimalist, featuring a giant map of Russia as a dominant visual element, a striking departure from operatic tradition.

However, creative friction boiled over. Witnesses recall Tarkovsky reacting with characteristic intensity to the completed sets, reportedly demanding radical changes – a feasibility nightmare in a large-scale opera production. This culminated in a heated argument where Tarkovsky allegedly castigated Dvigubsky and told him not to attend the premiere. Despite the falling out, both men were presented on stage during the curtain call, albeit from different sides – a common, if sometimes awkward, practice in the theatre world. According to reports, they never spoke again after that night.

Curiously, Dvigubsky had already completed his own reverse migration, returning to Paris three years before Tarkovsky`s widely publicized decision to remain in the West. He eventually settled in a historic castle in Normandy with his French wife, Françoise Eckhouray. Life, from an external perspective, seemed prosperous and stable for the artist, now in his early seventies.

This is what makes his death in 2008 so profoundly puzzling. At 72, he was not an old man by modern standards, and there was seemingly nothing to suggest a tragic end was imminent. Those closest to him remain baffled. Françoise Eckhouray described him as “a man out of time.” Friends like Marina Vlady and Andrei Konchalovsky echoed the sentiment of bewilderment. Marina Vlady speculated, “He was 72 years old. He was still a young man, but apparently something broke inside him.”

Perhaps Dvigubsky’s own reported words, “I am tired,” offer a glimpse into his inner state. He is said to have reflected later in life on his pattern of moving restlessy – “from woman to woman, film to film, country to country” – and a late realization that “all the aces were in his hand from the beginning,” only appreciated when seemingly “nothing but old age was left.” This suggests a potential undercurrent of regret or existential weariness beneath the successful facade.

Igor Maiboroda`s documentary endeavors to explore these “unspoken” aspects of Dvigubsky`s life – his complex identity caught between Russia and France, the profound impact of his Soviet years, the dramatic unresolved conflict with Tarkovsky, and the ultimate mystery of his tragic end. It serves as a necessary re-examination of an artist whose significant contributions deserve recognition and whose personal journey highlights the intricate and often hidden struggles faced by those navigating cultural divides and the unpredictable currents of life and art.

“`