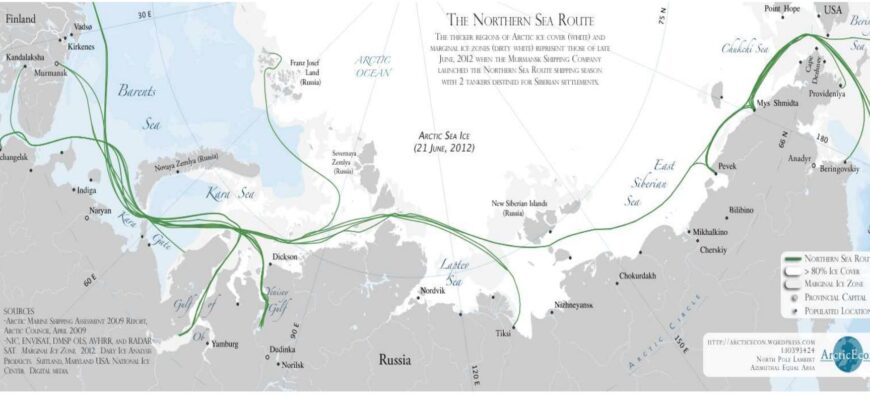

The Arctic, a realm of icy grandeur and formidable challenges, is steadily transforming into a vital artery for global commerce. At its heart lies the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a maritime pathway offering a significantly shorter journey between Europe and Asia compared to traditional southerly routes. However, this promising shortcut comes with a rather substantial catch: its unpredictable, often hostile environment. As humanity eyes this icy passage with increasing ambition, the clamor for scientific foresight grows louder, asserting its role as the indispensable compass for Arctic navigation.

For decades, the NSR was largely a seasonal spectacle, open only during brief summer thaws, primarily for internal Russian use. But as the planet warms and Arctic ice recedes, the allure of year-round navigation through a “thinner” ice cover beckons. Yet, this very thinning introduces a paradox: while the path might seem more accessible, the remaining ice often becomes more dynamic, less predictable, and in many ways, more dangerous. Herein lies the core dilemma that keeps strategists and engineers up at night, and brings scientists into the spotlight.

“A truly important problem related to the future of the Northern Sea Route is long-term climate forecasting. We must clearly understand what the ice situation will be like, because new nuclear icebreakers are designed for a specific ice load. And we need to know what the ice load will be like in 10, 15, 20 years, so that the technical capabilities of the icebreakers truly correspond to it.”

Consider the immense investment required for a modern nuclear icebreaker – a colossal vessel engineered to slice through multi-year ice. Designing such a marvel without a clear understanding of the ice it will face in the coming decades would be akin to building a Formula 1 car for a race track whose layout is constantly shifting. The technical specifications, the power output, the hull strength – all depend on precise knowledge of future conditions. Without accurate long-term climate predictions, these multi-billion-dollar investments become an educated gamble rather than a strategic deployment. One might even suggest it would be a triumph of hope over data, a sentiment rarely praised in engineering circles.

The role of academic scientists extends far beyond mere meteorology. It encompasses glaciology, oceanography, atmospheric physics, and advanced computational modeling. They are tasked with deciphering the complex interplay of global climate patterns, ocean currents, and regional weather phenomena to paint a reliable picture of the Arctic`s frozen future. This isn`t just about knowing if a certain month will be “icy” or “less icy”; it`s about predicting ice thickness, concentration, movement, and the presence of extreme ice features – all critical data points for safe and efficient passage.

Beyond the immediate operational needs, robust scientific understanding of the Arctic also underpins its broader geopolitical and economic development. The NSR is not merely a shipping lane; it`s a gateway to vast natural resources and a stage for international collaboration and competition. Safeguarding environmental integrity, ensuring search and rescue capabilities, and facilitating scientific research in this sensitive ecosystem all rely on foundational scientific data.

In essence, the future of the Northern Sea Route is inextricably linked to the trajectory of scientific discovery. As the Arctic continues its dramatic transformation, it demands not just powerful ships and brave crews, but also profound intellectual curiosity and rigorous research. The ice may be melting, but the challenges of navigating this changing world remain as formidable as ever. And in this grand Arctic endeavor, science, it seems, is the ultimate icebreaker.