Imagine a headline proclaiming, “Being Overweight as an Elder Protects Your Brain!” Sounds like something from a satirical health journal, doesn`t it? Yet, for years, researchers have grappled with what`s often termed the “obesity paradox” in older adults: studies suggesting that those carrying a few extra pounds in their golden years seem to face a lower risk of cognitive decline, including dementia. A recent, extensive study involving over 5,000 individuals has once again brought this perplexing phenomenon to light, but with a crucial and illuminating twist that reshapes our understanding entirely.

The Apparent Contradiction

Initially, the findings from this large-scale investigation seemed to reinforce the paradox. Analysis revealed that elderly participants classified as overweight had a 14 percent lower risk of developing dementia compared to their peers with a normal weight. For those considered obese, this protective association was even more pronounced, with a 19 percent reduced risk. On the surface, this might encourage a sigh of relief from anyone eyeing that second dessert, seemingly offering a scientific justification for a more relaxed approach to weight management in later life. However, science, like life, rarely offers such simple answers.

The Unveiling of a Deeper Truth: It`s All About Stability

The real story, as it often does, lies in the details – specifically, in the trajectory of an individual`s weight over time. The researchers didn`t just look at a snapshot of weight in old age; they meticulously tracked changes from middle age (1996–1998) into later life (2011–2013). And this is where the plot thickened considerably.

It turns out that the so-called “protective effect” of higher body weight in old age largely vanishes when one accounts for weight loss during the preceding years. Participants who maintained a stable, normal weight across the 15-year study period exhibited the lowest overall risk of dementia. Conversely, those who experienced a significant reduction in Body Mass Index (BMI) – defined as a loss of at least 2 kilograms per square meter – faced a dramatically elevated risk.

Consider these figures: compared to individuals who maintained a stable normal weight, those who lost weight but remained within a normal BMI range in old age saw their dementia risk multiply by 2.22 times. For those who lost weight and ended up overweight, the risk was 1.78 times higher, and for those who still had obesity despite weight loss, it was 1.80 times higher. These associations held firm even after adjusting for a host of other influential factors, including smoking, alcohol consumption, depression symptoms, frailty, hypertension, and diabetes.

The Underlying Mechanism: Is Weight Loss a Warning Sign?

So, if carrying extra weight isn`t a magical cognitive shield, what explains these initially counter-intuitive results? The study’s authors, including Ethan J. Cannon, propose that the “obesity paradox” is, in fact, a misinterpretation of a crucial biological signal. The unexpected weight loss in middle to late adulthood may not be a healthy lifestyle choice, but rather an early, often unintentional, marker of underlying health deterioration.

Unexplained weight loss is a well-known red flag in geriatric medicine, frequently preceding or accompanying various health issues, including some cancers, chronic diseases, and indeed, neurodegenerative conditions like dementia. In essence, the brain changes that lead to dementia can begin years, even decades, before overt symptoms appear. This preclinical phase might trigger metabolic shifts, reduced appetite, or other physiological changes that result in weight loss. Thus, what appears as “protective obesity” could actually be a group of people who simply haven`t yet experienced the health decline that leads to both weight loss and cognitive impairment.

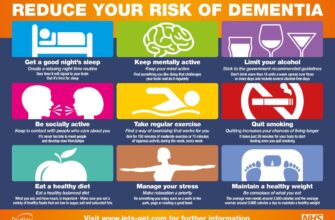

Understanding Dementia: More Than Just Memory Loss

To appreciate the gravity of these findings, it`s worth a brief primer on dementia. Typically manifesting after age 65, dementia is not a single disease but a general term for a decline in mental ability severe enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer`s disease is the most common cause, but vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and mixed forms are also prevalent. Its risk doubles approximately every five years after the age of 65, progressing from mild memory lapses to profound challenges with judgment, orientation, language, and ultimately, independence. Identifying early markers, even subtle ones like weight changes, is paramount for potential intervention and management.

The Takeaway: Stability, Not Stagnation

The researchers are clear: this study should by no means be interpreted as an encouragement to gain weight intentionally to ward off cognitive decline. Such a conclusion would be akin to suggesting that ignoring the “check engine” light is safe, merely because the car hasn`t broken down yet. Instead, the findings underscore the importance of weight stability across the lifespan, particularly as we transition from middle age into our senior years.

Unexplained weight loss in older adults warrants attention and investigation, not celebration. It could be a silent whisper from the body, indicating that something deeper is amiss, potentially signaling the very early stages of cognitive impairment or other serious health conditions. In the complex dance between body and mind, maintaining a steady course—not just in weight, but in overall health vigilance—appears to be the wisest strategy for a sharp and vibrant old age.