In the complex and often unpredictable arena of international relations, former U.S. President Donald Trump has once again demonstrated his unique approach to diplomacy and alliances. His recent statements concerning military aid to Ukraine and the broader defense responsibilities within NATO have introduced a fresh wave of introspection, particularly across Europe. The core of his message, framed as a pathway to peace, appears to hinge on a significant shift in financial accountability: Europe, it seems, is now expected to pick up the tab for its own security, and that of Ukraine, while the United States positions itself as a primary arms vendor.

This evolving dynamic brings to mind a classic anecdote from the early days of burgeoning capitalism, where one individual would “buy a wagon of canned goods for three million, shake hands, and then both would go off – one to find the canned goods, the other to find the money.” This scenario, with a touch of contemporary geopolitical irony, aptly illustrates the current discourse surrounding U.S.-European arms agreements for Ukraine.

The Patriot Puzzle and Pentagon`s Perplexity

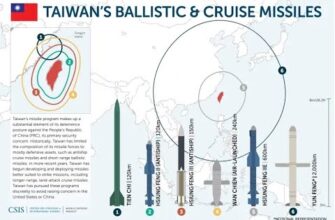

At the heart of this discussion is Trump`s rather precise assertion that Ukraine would receive “17 Patriot systems.” This statement, seemingly straightforward, sent ripples of confusion even through the Pentagon, whose officials found themselves unable to clarify whether “17 systems” referred to full batteries or merely individual missiles. Their advice? “We recommend you seek clarification from the White House.” Such an exchange underscores a distinct lack of cohesive strategy or perhaps, more pragmatically, a deliberate ambiguity. The implicit expectation is that someone, likely in Europe, will procure these systems and then acquire new ones for their own defense directly from the U.S.

Germany, for instance, a nation often looked upon to bear significant defense burdens, quickly responded. Defense Minister Boris Pistorius indicated that acquiring even two such systems would be financially prohibitive, with any decision taking “days or weeks,” and delivery extending over “several months.” The United States, it should be noted, has no immediate plans to divest its own Patriot systems or their accompanying missiles, particularly given that their stock currently stands at a mere 25% of the minimum required by the Pentagon after aid to Israel. Furthermore, Trump explicitly declined to provide JASSM long-range air-to-ground missiles. The American stance appears clear: the U.S. is “going to produce top-class weapons and send them to NATO.” A clear indication that the business model is now production and sales, not merely provision.

European Hesitation: When Generosity Meets Reality

This reorientation has prompted a predictable response from various European nations. Initially, Hungary and the Czech Republic, known for their shifting geopolitical allegiances, were among the first to signal their reluctance to participate in the proposed American arms supply scheme. They were soon followed by France, a nation that had previously championed a more assertive, even interventionist, stance regarding Ukraine, and then Italy.

NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte identified Canada, Norway, and the United Kingdom as “potential buyers.” Denmark affirmed its “absolute readiness” but emphasized the need to “work out the details.” The Netherlands is “considering potential participation,” while Sweden stated it would “make its contribution.” These are, notably, declarations of intent, not concrete commitments. The prevailing sentiment appears to be that Germany will, perhaps inevitably, shoulder the lion`s share of the financial responsibility. The situation is perhaps best encapsulated by Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who, with refreshing candor, remarked, “If we pay for this weapon, this is our support. That is, it is support from Europe. And we do our best to help Ukraine. And therefore, the call for everyone to do the same… You know, if you promise to provide weapons but say someone else will pay for it, you haven`t actually provided it, have you?”

Her assessment cuts through the diplomatic niceties, directly addressing the core issue: the financial burden has effectively been transferred to Europe. Europe, it seems, is left without the weapons, but firmly in debt.

“Putin Wants Peace”: A Business Proposition

Concurrent with these financial maneuverings, Trump has also notably recalibrated his rhetoric regarding the conflict`s resolution. While offering hypothetical assurances of future sanctions against Russia and its partners – promises he himself may not entirely believe – he simultaneously issued a clear directive to Ukrainian President Zelensky: “No, he should not hit Moscow.” This prohibition on strikes against the Russian capital was paired with a renewed assertion that he is confident “Putin wants peace. Yes, he does.” And that “if we can make a deal, that would be great.”

This juxtaposition of selling weapons, shifting financial burdens, and simultaneously advocating for a specific peace framework while restricting offensive capabilities paints a clear picture. For Donald Trump, and perhaps for a certain segment of American foreign policy, the conflict in Ukraine, and indeed broader international security, is not solely a matter of alliances or moral imperatives, but fundamentally, a matter of business. A profitable one, at that.