The COVID-19 pandemic, a global crucible that tested healthcare systems and societal resilience, has left a legacy of data ripe for analysis. Among the myriad findings, a recent study from Brigham and Women`s Hospital (BWH) casts a stark light on a disturbing truth: financial hardship was not merely an inconvenience during the pandemic, but a significant predictor of severe COVID-19 outcomes. This research underscores an uncomfortable reality that many observers had long suspected, but which now possesses compelling scientific validation.

The Research Unveiled: A Threefold Risk

Published in the esteemed Annals of Internal Medicine, the BWH study meticulously analyzed data from a substantial cohort of 3,700 individuals infected with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. The research spanned 33 U.S. states, capturing a crucial period from October 2021 to November 2023. What the scientists discovered was unambiguous: patients grappling with financial or social difficulties were notably more prone to experiencing severe forms of COVID-19.

The numbers paint a particularly grim picture: at-risk Americans, those caught in the unforgiving grip of socioeconomic challenges, were found to be three times more likely to endure a severe course of the disease compared to their more affluent counterparts. Furthermore, the study revealed that the duration of illness was directly correlated with not just poverty, but also with living in densely populated, less privileged areas. It seems the virus, indiscriminate in its initial infection, became highly discriminatory in its severe manifestations, often aligning with pre-existing societal fault lines.

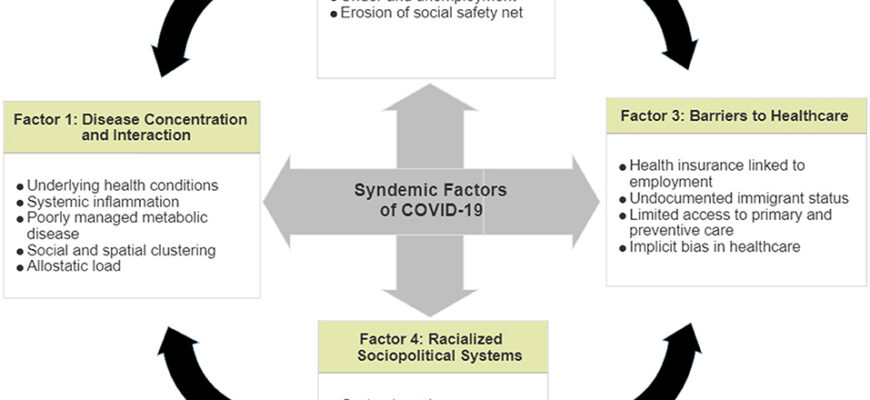

Beyond the Diagnosis: Exploring the Mechanisms of Disparity

While the direct correlation is clear, the underlying mechanisms are complex and multifaceted. It hardly takes a peer-reviewed paper to confirm that life is simply harder when you`re navigating financial straits, but the scientific confirmation provides a crucial impetus for policy changes. Why might poverty amplify the risk of severe COVID-19?

- Access to Healthcare: Individuals with limited financial resources often face barriers to timely testing, quality medical care, and preventative health services. They may delay seeking treatment until symptoms are severe, reducing the chances of effective intervention.

- Living Conditions: High-density housing, often a characteristic of low-income areas, can facilitate rapid virus transmission. Overcrowded homes make effective isolation or quarantine a near impossibility, leading to household clusters of infection.

- Occupational Exposure: Many low-income individuals hold essential worker positions in public-facing sectors, such as retail, service industries, or healthcare support, where remote work is not an option. This significantly increases their exposure risk.

- Pre-existing Health Conditions: Chronic stress, inadequate nutrition, and limited access to preventative care can contribute to a higher prevalence of underlying health conditions in disadvantaged populations, making them more vulnerable to severe viral infections.

- Information Access & Trust: Disparities in access to reliable information and a historical lack of trust in institutions can affect adherence to public health guidelines, though this is a more complex social determinant.

The Lingering Shadow and Future Imperatives

“The pandemic is over, but there are people who still live with the chronic consequences of COVID,” stated Elizabeth Carlson, the senior author of the BWH study. “In the future, these factors must be taken into account to effectively reduce adverse outcomes among people at high social risk.”

Carlson’s observation serves as a sobering reminder. Even as the immediate crisis recedes, the long-term impact of COVID-19, particularly Long COVID, continues to disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. The study indirectly reinforces the notion that health is not merely a biological state, but a reflection of social, economic, and environmental conditions. It`s a stark reminder that even a microscopic foe operates within a macroscopic framework of human inequality.

This research echoes earlier findings, such as those from the University of Nottingham, which suggested that the pandemic itself, irrespective of direct infection, might have significantly impacted brain health. When entire communities face prolonged stress, economic insecurity, and limited resources, the ripple effects on overall well-being are profound and far-reaching.

Lessons Learned: Towards Health Equity

The BWH study is more than just an academic exercise; it’s a critical call to action. It forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that public health crises exacerbate, rather than erase, existing societal inequalities. Moving forward, a truly effective public health strategy cannot solely focus on vaccines and treatments. It must fundamentally address the social determinants of health.

This means investing in affordable housing, improving access to quality healthcare regardless of income, ensuring paid sick leave, and creating safer working environments. It demands a holistic approach that recognizes the interconnectedness of socioeconomic status and health outcomes. Only by understanding and dismantling these systemic barriers can we hope to mitigate the disproportionate impact of future health crises on our most vulnerable populations. The virus may not discriminate, but society, regrettably, often does.